Two Americans and a German share Chemistry Nobel

08 Oct 2014

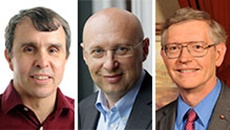

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2014 has been awarded jointly to Eric Betzig, Stefan W Hell and William E Moerner "for the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy", which extended the nanodimensions of optical microscopy.

Eric Betzig of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Ashburn, William E Moerner from the University of Stanford (both American) and Stefan W Hell from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Gottingen, Germany were awarded the 2014 Nobel prize in chemistry for making "an optical microscope into a nanoscope".

Eric Betzig of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Ashburn, William E Moerner from the University of Stanford (both American) and Stefan W Hell from the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Gottingen, Germany were awarded the 2014 Nobel prize in chemistry for making "an optical microscope into a nanoscope".

''For a long time optical microscopy was held back by a presumed limitation: that it would never obtain a better resolution than half the wavelength of light. Helped by fluorescent molecules the Nobel Laureates in Chemistry 2014 ingeniously circumvented this limitation. Their ground-breaking work has brought optical microscopy into the nanodimension,'' the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said in its announced on Wednesday.

The prize was given "for the development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy".

"It (the discovery) opens entirely new possibilities for chemistry and for biochemistry," Professor Sven Lidin, chairman of the Nobel Committee said in an interview with freelance journalist Joanna Rose immediately after the announcement.

Eric Betzig is with the Janelia Farm Research Campus, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Ashburn, Vancover, USA and William E Moerner teaches at the Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA while Stefan W Hell is attached to the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen, and the German Cancer Research Center at Heidelberg, Germany.

In what has become known as nanoscopy, scientists visualise the pathways of individual molecules inside living cells. They can see how molecules create synapses between nerve cells in the brain; they can track proteins involved in Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and Huntington's diseases as they aggregate; they follow individual proteins in fertilised eggs as these divide into embryos, the awards committee noted.

It was all but obvious that scientists should ever be able to study living cells in the tiniest molecular detail. In 1873, the microscopist Ernst Abbe stipulated a physical limit for the maximum resolution of traditional optical microscopy: it could never become better than 0.2 micrometres. But Eric Betzig, Stefan W Hell and William E Moerner made it possible to use the optical microscope to peer into the nanoworld.

They have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2014 for having bypassed this limit.

The award recognises two separate principles. One enables the method stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy, developed by Stefan Hell in 2000. Under this, two laser beams are utilised - one stimulates fluorescent molecules to glow, another cancels out all fluorescence except for that in a nanometre-sized volume. Scanning over the sample, nanometre for nanometre, yields an image with a resolution better than Abbe's stipulated limit.

Eric Betzig and William Moerner, working separately, laid the foundation for the second method, single-molecule microscopy. The method relies upon the possibility to turn the fluorescence of individual molecules on and off. Scientists image the same area multiple times, letting just a few interspersed molecules glow each time. Superimposing these images yields a dense super-image resolved at the nanolevel. In 2006 Eric Betzig utilised this method for the first time.

Today, nanoscopy is used world-wide and new knowledge of greatest benefit to mankind is produced on a daily basis.

In fact, scientists these days use computers to carry out experiments that yield a much deeper understanding of how chemical processes play out. Computer models mirroring real life have become crucial for most advances made in chemistry today.