From a flat mirror, designer light

06 Sep 2011

Exploiting a novel technique called phase discontinuity, researchers at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) have induced light rays to behave in a way that defies the centuries-old laws of reflection and refraction.

The discovery, published this week in Science, has led to a reformulation of the mathematical laws that predict the path of a ray of light bouncing off a surface or traveling from one medium into another - for example, from air into glass.

"Using designer surfaces, we've created the effects of a fun-house mirror on a flat plane," says co-principal investigator Federico Capasso, Robert L. Wallace Professor of Applied Physics and Vinton Hayes Senior Research Fellow in Electrical Engineering at SEAS.

"Our discovery carries optics into new territory and opens the door to exciting developments in photonics technology."

It has been recognised since ancient times that light travels at different speeds through different media.

Reflection and refraction occur whenever light encounters a material at an angle, because one side of the beam is able to race ahead of the other. As a result, the wavefront changes direction.

The conventional laws, taught in physics classrooms worldwide, predict the angles of reflection and refraction based only on the incident (incoming) angle and the properties of the two media.

While studying the behaviour of light impinging on surfaces patterned with metallic nanostructures, the researchers realised that the usual equations were insufficient to describe the bizarre phenomena observed in the lab.

|

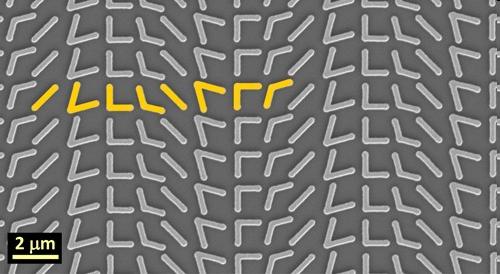

| Electron micrograph of an array of gold antennas on a silicon surface. The array is created by repeating the sequence in yellow across the entire surface. Each antenna has a thickness of 50 nanometers (50 billionths of a meter). The scale bar is in microns, its length slightly shorter than a ten-thousandth of an inch. Image courtesy of Nanfang Yu. |

"Ordinarily, a surface like the surface of a pond is simply a geometric boundary between two media, air and water," explains lead author Nanfang Yu (PhD '09), a research associate in Capasso's lab at SEAS. "But now, in this special case, the boundary becomes an active interface that can bend the light by itself."

The key component is an array of tiny gold antennae etched into the surface of the silicon used in Capasso's lab. The array is structured on a scale much thinner than the wavelength of the light hitting it. This means that, unlike in a conventional optical system, the engineered boundary between the air and the silicon imparts an abrupt phase shift (dubbed "phase discontinuity") to the crests of the light wave crossing it.

Each antenna in the array is a tiny resonator that can trap the light, holding its energy for a given amount of time before releasing it. A gradient of different types of nanoscale resonators across the surface of the silicon can effectively bend the light before it even begins to propagate through the new medium.

The resulting phenomenon breaks the old rules, creating beams of light that reflect and refract in arbitrary ways, depending on the surface pattern.

|

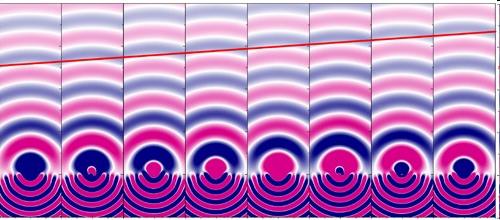

| An array of nanoscale resonators, much thinner than a wavelength, creates a constant gradient across the surface of the silicon. In this visualization, the light ray hits the surface perpendicularly, from below. The resonators on the left hold the energy slightly longer than those on the right, so the wavefront (red line) propagates at an angle. Without the array, it would be parallel to the surface. Image courtesy of Nanfang Yu. |

"By incorporating a gradient of phase discontinuities across the interface, the laws of reflection and refraction become designer laws, and a panoply of new phenomena appear," says Zeno Gaburro, a visiting scholar in Capasso's group who was co-principal investigator for this work. "The reflected beam can bounce backward instead of forward. You can create negative refraction. There is a new angle of total internal reflection."

Moreover, the frequency (color), amplitude (brightness), and polarization of the light can also be controlled, meaning that the output is in essence a designer beam.

The researchers have already succeeded at producing a vortex beam (a helical, corkscrew-shaped stream of light) from a flat surface. They also envision flat lenses that could focus an image without aberrations.