Mapping the distribution of dark matter in our galaxy

25 Mar 2011

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute astronomer Heidi Newberg is using a new grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to begin mapping the distribution of dark matter in our galaxy. The more than $382,000 grant will utilize the massive computing power of the international MilkyWay@Home project to help uncover the whereabouts of the elusive dark matter and provide another piece in the puzzle to map the Milky Way.

|

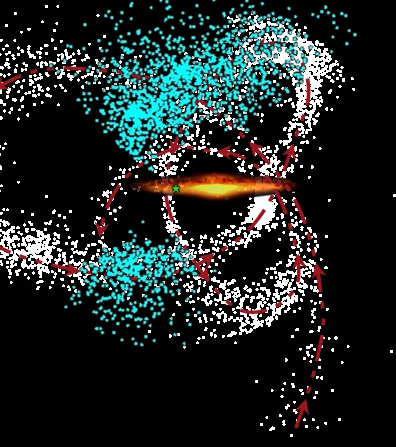

| A simulation developed with MilkyWay@Home shows the formation of several stellar streams (Sagittarius, Orphan, and GD-1) around the Milky Way. The animation represents four billion years in the Milky Way, ending at the present day. Credit: Rensselaer/Benjamin A. Willett |

Any third grader can tell you the order of the planets from the sun, but astronomers know surprisingly little about exactly how and where the mass in our galaxy is distributed across the cosmos. One large conundrum with the effort to map the Milky Way is that much of the known mass of the galaxy is completely unaccounted for. Add up the planets, sun, stars, moons, asteroids, and other known mass and only a fraction of the mass is accounted for.

Many scientists purport that the difference is made up by the presence of dark matter, which is undetectable to all modern telescopic technology. But Newberg thinks that with MilkyWay@Home, the computer may be able to accomplish what no telescope has done before – show astronomers where dark matter is likely to reside in the galaxy.

Led by researchers at Rensselaer, the MilkyWay@Home project is among the fastest distributed computing programs ever in operation. At its peak, it has run at a combined computing power of over 2 petaflops donated by a total of 93,206 people in 195 countries and counting. That is more countries than the United Nations. The combined computing power of all these personal computers, which rivals the most powerful supercomputers in the world, is being used by researchers like Newberg to uncover some important and basic things about our galaxy.

''MilkyWay@Home is allowing us to consider bigger thinking when it comes to understanding the galaxy,'' said Newberg, who is professor of physics, applied physics, and astronomy at Rensselaer. ''With this grant we will combine my previous research mapping tidal debris streams with the power of MilkyWay@Home to simulate the creation of these streams and begin, very importantly, to start to constrain the properties of dark matter.''

Tidal debris streams, also called stellar streams, are the scattered remains of dwarf galaxies that have been ripped apart after coming too close to a larger galaxy such as the Milky Way. Several of these glowing streams currently orbit the Milky Way as part of what is aptly called the galactic halo.