Microreactors: small scale chemistry could lead to big improvements for biodegradable polymers

17 May 2011

Using a small block of aluminum with a tiny groove carved in it, a team of researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the Polytechnic Institute of New York University is developing an improved ''green chemistry'' method for making biodegradable polymers.

|

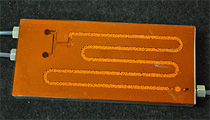

| Typical NIST microreactor plate for studying enzyme catalyzed polymerization. The aluminum plate, topped with a transparent film, is approximately 40 millimeters by 90 mm. The channel, filled with plastic beads carrying the enzyme catalyst, is 2 mm wide and 1 deep. Credit: Kundu, NIST |

Their recently published work is a prime example of the value of microfluidics, a technology more commonly associated with inkjet printers and medical diagnostics, to process modeling and development for industrial chemistry.

''We basically developed a microreactor that lets us monitor continuous polymerisation using enzymes,'' explains NIST materials scientist Kathryn Beers. ''These enzymes are an alternate green technology for making these types of polymers - we looked at a polyester - but the processes aren't really industrially competitive yet,'' she says.

Data from the microreactor, a sort of zig-zag channel about a millimetre deep crammed with hundreds of tiny beads, shows how the process could be made much more efficient. The team believes it to be the first example of the observation of polymerisation with a solid-supported enzyme in a microreactor.

The group studied the synthesis of PCL, a biodegradable polyester used in applications ranging from medical devices to disposable tableware. PCL, Beers explains, most commonly is synthesised using an organic tin-based catalyst to stitch the base chemical rings together into the long polymer chains. The catalyst is highly toxic, however, and has to be disposed of.

Modern biochemistry has found a more environmentally-friendly substitute in an enzyme produced by the yeast strain Candida antartica, Beers says, but standard batch processes - in which the raw material is dumped into a vat, along with tiny beads that carry the enzyme, and stirred - is too inefficient to be commercially competitive. It also has problems with enzyme residue contaminating and degrading the product.