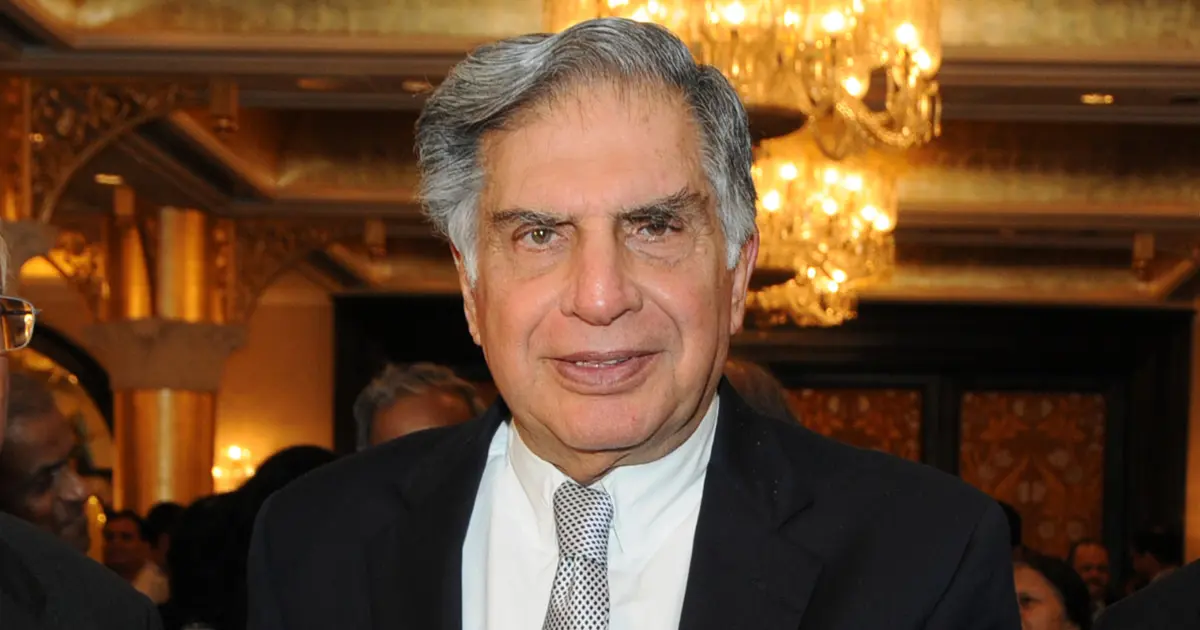

The remarkable Ratan Tata

By Kiron Kasbekar | 23 Oct 2024

One newspaper report of Ratan Tata’s passing away showed an old photo of him climbing into the cockpit of a Lockheed Martin F-16 fighter.

The photo brought back memories of the Aero India show in Bengaluru which I’d gone to cover in 2007 on behalf of domain-b.com. That was when a 69-year-old Tata flew the F-16 fighter.

It was one of the biggest attractions for the crowds milling about in the spectators’ enclosure. India’s top businessman flying a fighter aircraft! Wow!

I had read and heard about Tata being a trained pilot who loved to fly a company plane, usually a light executive jet. But it was the first time I saw him taking off and flying in a plane – and a fighter jet at that!

Of course, Lockheed Martin didn’t want to take chances, and there was an American co-pilot who served as a back-up and did the actual controls when they went through some amazing aerobatic maneuvers that would have made most people dizzy.

“An unbelievable experience,” Tata called it, describing the stunts the American co-pilot took the plane through. It must have been a heady experience, if not a dizzy one.

The next day, Tata flew another plane. This time it was a Boeing F-18 Super Hornet, a bigger and more powerful aircraft than the F-16. The experience must have been as exhilarating as the one the previous day.

Focused

Flying was not a new thing for the Tata group chairman. He had started flying in his late teens when he was studying in America, where he spent a decade of his life at the time. This was during the 1960s, when he was studying at Cornell University.

Of course, in the beginning he was not permitted to fly solo, and had to have an instructor as co-pilot. But after a few years he was able to fly solo. And he demonstrated his abilities as a pilot.

One day, Tata decided to take his classmates for a round in a single-engine Tri-Pacer aircraft. They took off well, but the aircraft soon developed an engine failure. A calm and composed Tata safely executed an emergency landing aircraft at the Ithaca Tompkins International Airport.

That calmness in the face of crises and the need to make tough decisions characterized Tata’s career journey over the next decades until his passing.

The year 2007, when he flew the American fighter jets, was also one in which Tata Advanced Systems Limited, an aerospace manufacturing, military engineering and defense technology company, was launched. TASL is a fully-owned subsidiary of Tata Sons, the group’s holding company.

TASL was only one of the many high-tech ventures Tata invested in from the time he took over as chairman of the group in 1991.

Early thoughts

Tata’s ideas about the group’s business reorganization had crystalized many years earlier. When Rajiv Gandhi became prime minister of India in 1984 and began the process of liberalizing the rigid licensing laws that then governed industry, Tata, who was nowhere near the top among the Tata group top brass, began making ambitious plans for the future of the group.

Not only were the plans ambitious in terms of the scope and reach of the projects he had in mind, they were also highly ambitious in terms of how the Tata Group itself would have to be reorganized, restructured, and reoriented. They required stepping on many toes at the top of the group’s hierarchy.

No Indian group has restructured itself as radically as Tata did after the reorganization plans came into effect after 1991.

In 1984 I used to edit a business magazine called Business Update, a cooperative venture of a group of about thirty journalists and other professionals I had brought together, with small equity amounts from each, all of it adding up to so little (about Rs.3 lakh) that we ran out of funds almost before we launched the magazine. A sum of Rs.3 lakh in 1983-84, when we started the company, would be equivalent to about Rs.50 lakh in 2024.

We had a staff of over 25 people. For a few months most of the staff (all the senior and mid-level staff) worked without salaries; and our creditors (paper supplier, processor, printer, etc.) were kind enough to not push for their payments and still continued providing their services.

Just around that time, in the middle of 1984, Basudev Das, one of my colleagues in the magazine, got wind of the Tata Plan, which was still under wraps, and had requested Ratan Tata’s office for an interview for the feature. We did the interview, and put together a longish feature article.

That was the exact time when we were forced to halt production. It took me three months to raise additional funds, and we re-launched the magazine with a dramatic cover designed by Rediffusion, the ad agency. The big title on the cover was The Tata Plan.

The extraordinary thing was not the cover feature we did, although it was a damn good story. What was extraordinary was that since Ratan Tata had agreed to an exclusive interview, he waited for our magazine to relaunch.

I think almost any other businessman would have arranged an interview with a major newspaper or magazine. But Tata did not give an interview to any other publication. He considered his word more important, and our interview was absolutely exclusive, even three months after we had spoken to him.

More than a decade later, when, after being stung by a critical article in a news magazine, Tata had stopped giving interviews to the press, I sought an interview with him. I was Editor of The Economic Times’ Bombay edition then, the paper’s flagship edition; and sometime in 1995 I sent a message to the Tata head office that I wished to interview him. He agreed, and I was the first Indian journalist he gave an interview to, after that break. After that he gave interviews to other publications too.

In the interview he gave me he spoke about the way the group was headed. It was like the ‘After’ part of a ‘Before and after’ story, the ‘Before’ part being the story we’d carried in Business Update magazine in 1984. He had achieved a great deal in the interim –radically restructured the group, something he had said in 1984 that he wanted to do.

Restructuring begins

Before Ratan took charge, the group was divided into different satrapies, in the steel business, in hotels, in chemicals, soaps and detergents, edible oils, consumer durables, pharmaceuticals, paints, in consumer products. The group chairman, J R D Tata, was highly respected, and there was no clash with him, but that was more because JRD kept an arm’s length relationship with these satrapies.

After Rata Tata took charge in 1991, the group restructuring began, and went on non-stop. Companies that were not part of the plan were gradually sold off, and the proceeds of the disinvestment scaled up the group’s kitty for expansion of select existing businesses and launch of new businesses. In the process Ratan Tata had to step on many toes, including, most visibly, those of the entrenched satraps who bossed over the group’s biggest companies. But he did not waver from his resolve to restructure the group’s businesses.

The group gave up soaps and detergents, edible oils, textiles, fertilizers, cement, cosmetics, and some other businesses it had been running for decades. That was how the group was able to raise funds to strengthen and expand a few existing businesses where it had core strengths, and to invest in new areas.

The most daring feat was the launch of the group’s own car. Designed and manufactured in-house, with no foreign assistance. No other Indian automobile company had launched a successful new passenger car.

The Indica (that word being derived from ‘Indian Car’) was launched on 30th December 1998 as a hatchback with a diesel engine. It was introduced in an ad campaign with the slogan ‘More car per car’, the ad campaign focusing on the car’s roomy interiors as well as its affordability.

Within a week of its unveiling in 1999, Tata Motors received 115,000 orders against full payment. Within two years, the Indica became the number-one car in its segment.

The ill-fated Nano

Then came the Nano. Envisioned by Ratan Tata as a low-priced car that many more Indians would be able to afford, compared to the vehicles in the market – almost a ‘people’s car’.

The Nano was expected to be launched from a place called Singur, roughly 40 km from Kolkata. Unfortunately, while West Bengal’s Left Front government facilitated the launch of the project, and allotted the required land, Trinamool Congress leader Mamata Banerjee started a protest movement against it in 2006. Tata was compelled to give up the project and move it to Sanand in Gujarat, where it could begin production only in 2010. Four precious years were lost.

Tata had believed he was creating a vehicle that was a safer alternative to a scooter or motorbike, the vehicles of choice of the middle-middle class those days, when car ownership was very, very low, nowhere near today’s levels. The car, with its spacious interior, would have been ideal for a four-member Indian middle-class family. Its funky design and colors were actually quite attractive.

A 2008 study by CRISIL, the Indian credit rating agency, predicted that the Nano would expand the nation's car market by 65%. That remained a pipedream.

The Nano's anticipated debut had a major impact on the used car market, where prices dropped 25-30% before the Nano launch. Sales of the Maruti 800, its Nano’s closest competitor, declined 20% immediately following the Nano's unveiling. That’s how impressive the Nano project looked first.

The company’s marketing strategy seemed perfect. But then it all fell apart. One, because the company had cut down on some costs it considered ‘luxury’ it began to be seen and labeled as ‘cheap’. Which was not how Ratan Tata saw it. He saw it as a ‘people’s car’. Almost like how the Volkswagen Beetle was born, without the political connotations.

But the delays and bad publicity that resulted from the brouhaha in West Bengal set the company back badly. And, although it tried its best to improve the car’s features to take care of the negative comments it had attracted, it had lost valuable time.

Sadly for all these reasons, the Nano failed to disrupt the market as expected. On the contrary it was seen as a big failure. By late 2012, news reports revealed that Indian consumers had shown limited enthusiasm for the car. Sales in the first two fiscal years after its launch remained steady at around 70,000 units, despite Tata's intention to maintain a production capacity of 250,000 units per year.

In July 2012, Ratan Tata, the then-chairman of the Tata Group, acknowledged that the Nano had immense potential in developing countries but admitted that early opportunities had been missed due to initial problems. Production was brought to a halt in May 2018.

Major changes

The Nano and the Indica (and other vehicles that followed) were only a part of Ratan Tata’s strategy. He had already completed the most difficult part of his plan – the selling off of several businesses.

No other Indian businessman has restructured a big business group the way Ratan Tata did.

In 1998 Merind Ltd, the group’s pharmaceuticals company, was sold to Wockhardt Ltd. In the same year the home appliances division of Voltas Ltd was transferred to a joint venture with Electrolux because Voltas decided to narrow its focus to commercial air-conditioning and refrigeration.

In 1999 Goodlass Nerolac Paints Ltd was sold to Japan’s Kansai Paint Co. In 2000 the group exited its cement company, ACC Ltd, selling its remaining shares to Ambuja Cements Ltd.

In 2004 the group sold its telecom hardware company Tata Telecom to Avaya LLC because it focus on telecom services, which led it to acquiring the public sector Videsh Sanchar Nigam Ltd (now Tata Communications).

Tinplate Company of India was merged with Tata Steel in January 2024. Tata Metaliks was merged with Tata Steel in February 2024. Four other companies (Tata Steel Mining Ltd, Tata Steel Long Products Limited, S&T Mining Company Limited, and Tata Metaliks Limited) have been merged with Tata Steel. And three other companies were expected to be merged in the near future.

The disinvestments were made with a purpose – to put accumulate enough funds to expand the group through acquisitions in its areas of interest. So there were acquisitions, which would not have been possible had the group not sold off non-strategic assets. Among the biggest acquisitions were:

- Tetley Tea (2000): The acquisition of Tetley for $431 million made Tata Tea (now Tata Global Beverages) the second-largest tea company in the world. This was one of India’s first large overseas acquisitions.

- Corus Steel (2007): Tata Steel acquired Corus, a European steel giant, for $12.9 billion, making Tata Steel the world’s fifth-largest steel producer.

- Jaguar Land Rover (2008): Ratan Tata oversaw Tata Motors’ purchase of the iconic British brands Jaguar and Land Rover for $2.3 billion, a move that revitalized both brands and became a major success story for Indian manufacturing globally.

While the Tata group has grown through acquisitions, each of its acquisitions has been chosen to fit into the group’s existing businesses, and to expand them. During the 21 years Ratan Tata headed the Tata Group, group revenues expanded over 40 times, and profit over 50 times.

The group continued to grow even after he relinquished charge, and today, under the leadership of Natarajan Chandrasekaran, the group continues to grow.

In 2023-24, the revenues of Tata companies, taken together, were more than $165 billion. These companies collectively employ over 1 million people.

Businessman with a heart

Ratan Tata was more than a successful businessman. He was a businessman with a heart. Always polite and soft-spoken in his dealings with people, big and small, a big corner of his heart was always beating for hapless animals.

He had allowed stray dogs to enter the group headquarters, and built a room for them on the ground floor. But that was nothing compared to the shelters and modern, well-equipped animal hospitals he built.

This was in addition to the donations Tata made to hospitals for people, and to educational and research institutions in India and in America.

Ratan Tata was not in the list of the top richest businessmen in India, let alone in the world. For he did not pile up his riches, despite being in a position to do so. And most of what he received he gave away to charity.

An amazing achievement by an amazing man.