New algorithm could substantially speed up MRI scans

01 Nov 2011

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) devices can scan the inside of the body in intricate detail, allowing clinicians to spot even the earliest signs of cancer or other abnormalities. But they can be a long and uncomfortable experience for patients, requiring them to lie still in the machine for up to 45 minutes.

Now this scan time could be cut to just 15 minutes, thanks to an algorithm developed at MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics.

Now this scan time could be cut to just 15 minutes, thanks to an algorithm developed at MIT's Research Laboratory of Electronics.

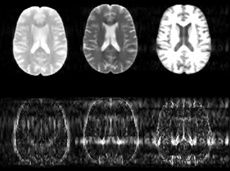

MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields and radio waves to produce images of the body. Rather than taking just one scan of a patient, the machines typically acquire a variety of images of the same body part, each designed to create a contrast between different types of tissue. By comparing multiple images of the same region, and studying how the contrasts vary across the different tissue types, radiologists can detect subtle abnormalities such as a developing tumor. But taking multiple scans of the same region in this way is time-consuming, meaning patients must spend long periods inside the machine.

In a paper to be published in the journal Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, researchers led by Elfar Adalsteinsson, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science and health sciences and technology, and Vivek Goyal, the Esther and Harold E Edgerton Career Development Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, detail an algorithm they have developed to dramatically speed up this process. The algorithm uses information gained from the first contrast scan to help it produce the subsequent images. In this way, the scanner does not have to start from scratch each time it produces a different image from the raw data, but already has a basic outline to work from, considerably shortening the time it takes to acquire each later scan.

To create this outline, the software looks for features that are common to all the different scans, such as the basic anatomical structure, Adalsteinsson says. "If the machine is taking a scan of your brain, your head won't move from one image to the next," he says. "So if scan number two already knows where your head is, then it won't take as long to produce the image as when the data had to be acquired from scratch for the first scan."

In particular, the algorithm uses the first scan to predict the likely position of the boundaries between different types of tissue in the subsequent contrast scans. "Given the data from one contrast, it gives you a certain likelihood that a particular edge, say the periphery of the brain or the edges that confine different compartments inside the brain, will be in the same place," Adalsteinsson says.